Pension age extension: we’ll meet again

I’ve said it before, but old age is looking better and better for anyone who is getting closer to it.

Australia’s former treasurer and new Prime Minister Scott Morrison wants to make it better still. Last week, out of the blue, he announced the government would no longer fight to raise the pension age to 70 by 2035.

Morrison’s reasoning: "I believe that measure is no longer necessary. It will remain no longer necessary so long as we continue to keep the strong economic policies that see the growth continue." Literally, that was his whole explanation.

This is a backflip for a man who had backed the move ever since becoming treasurer. It’s widely seen as part of "clearing the decks" for an election expected next May.

So is this cynical politics or a recognition that the old policy had gone too far?

The change in being old

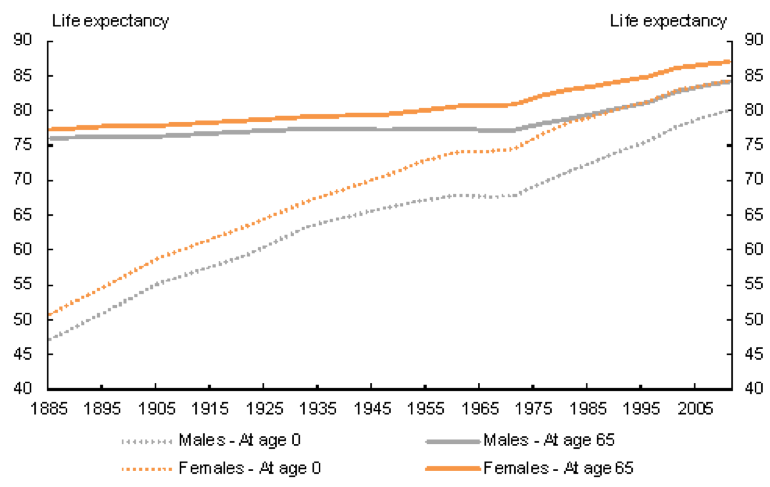

Male life expectancy at age 65 – the traditional age for receiving an age pension – was around 76 back in 1974, and it had moved up one or two years in the 65 years since Australia started paying for age pensions.

But in the 1970s we started to find ways to fight heart disease and other conditions of old age, we began talking people into giving up smoking, and so on. In the next 40 years, male life expectancy moved up eight years, to around 84. The rise in women’s life expectancy at 65 was almost as spectacular, up from 81 to 87. Both rates are projected to keep rising.

So while 1974’s average 65-year-old man had an average 11 years of life left, a 65-year-old in 2015 had almost 20 years of life ahead of him.

Note that these are average life expectancies. Life expectancies at age 0 (dotted lines) towards the left of the graph are skewed by higher rates of death in childhood.

Source: Australian Government Actuary, Australian life tables 2010–12

70 is the new 60

Not only that, but being 70 is a much better deal than it used to be. For the average person, it turns out that if you want to be reasonably active and capable, it’s not your age that matters. What matters is how close you are to death, which is a different thing when you think about it.

And the period at the end of your life when you need a lot of pricey health care is, if anything, shrinking slightly. Medical science has started reducing the rate of things like old-age dementia, which make decent functioning impossible, and which also scares the proverbial out of many of us.

So instead of having eight good years left at 65, as you did in 1974, these days you might have double that. If things keep going in the right direction this fast, in another couple of decades you could have 20 good years left.

The pension push

Over the past decade or two, many people have begun to think that the pension should be adjusted to account for this change. That not only shrinks government’s pension spending, but also ups the number of people working and paying taxes. As a bonus, a higher pension age improves people’s attitudes to a 65-year-old who wants to keep working.

In 2009, the Rudd government legislated to move the pension up from 65 to 67 between 2017 and 2023. It’s now 65 years and 6 months. The plan announced by the Abbott government in 2014 would have taken it to 70 by 2035. It never became law, and now Morrison plans to scrap it.

But the chances are that we haven’t seen the last of plans to raise the pension age beyond 67. This is because his claim that it’s "no longer necessary" looks pretty dubious:

- Life expectancies seem to just keep going up (though at some point that will probably change).

- People are staying in education longer and starting work later in their life.

- The long rise in the rates of older workers who are part of the workforce has ended.

So our future is one where more people on pensions are supported by fewer people in work. Governments will need to find fixes for that problem. At some point, another increase in the pension age is still likely to be one of them.

Two footnotes

I could stop there, but there are two other points worth making about the pension age.

The first point is that if Morrison’s backflip was aimed at attracting voters, it might not work that well. I was involved in the push to raise the pension age to 67, and I was surprised by how little pushback the Rudd government got against its 2009 decision to do just that. A lot of people seem to accept the argument for at least a slightly higher age.

The second point is this: some people involved in manual labour are just pretty much shot by 65, or even 60. In our current system, some of these people can go onto a disability support pension; others cannot.

To my surprise, when the Rudd government announced the initial rise in the pension age, it didn’t look at these arrangements. Neither did the Abbott government. An incoming Labor government might usefully examine whether we’re doing the right thing by these people.