A postcard from the future: Living in lockdown in France

Last Saturday, I popped into my favourite shop in Villefranche-sur-Mer, the village I call home just around the headland from Nice. Always smiling, the owner of Foccacaria Mei actually lives in the hills behind San Remo, across the border in Italy. Along with the best cold cuts and cheese cabinet for miles, Alessandro always has a selection of freshly-baked sweet treats endearingly made by his mum.

That day, he was uncharacteristically sombre. "You guys just don’t understand yet," he told me, waving to the groups of people strolling past his store. The next street down, in the main square, the restaurants were busy with lunchtime diners. He told me how in his village, because of coronavirus, people were no longer leaving their homes. "I drive home, lock my gates and don’t go out," he said. "The village is sprayed with disinfectant every evening."

Despite living so close to Italy, the truth is, I didn’t understand. My daughter and I were on our way to meet a friend and her daughter for a playdate at the beach.

Schools had been ordered to close as of Monday and we’d been told to practice social distancing but, on a hot early spring weekend, the last place people wanted to be was indoors. And my friend and I had discussed it; we wouldn’t be interacting with anyone but ourselves, so surely it was ok?

Later that evening, I started to get a sense of what he meant. Giving just under four hours’ notice, France’s Prime Minister Édouard Philippe ordered the closure of the country’s clubs, cafés, cinemas and restaurants. But the next day, people were still socializing in groups — if they couldn’t meet up in their favourite bars, it appears the French had decided to find the nearest park, canal or beach instead.

I underestimated how intimidating it would be to be stopped by the police along the streets you call home.

Four nights after his first live address, French President Emmanuel Macron made his second 8pm appearance to the nation. "We are at war," he warned. As of midday on Tuesday, we were ordered to stay at home for 15 days, only to leave if absolutely necessary.

Adapting to life in lockdown

Now, much of Europe — and other parts of the world — is in lockdown, but what exactly does that mean? Here in France, it translates to permission to leave our homes for a handful of "essential" reasons: the supermarket, the pharmacy and other health reasons, to visit those who need assistance or for children who need minding, and to briefly stretch our legs near to our homes. Work, also, if there’s no possibility to do so from home. We have to fill out a form (or handwrite it) each time we step out our front door. If you get caught by police without it and any identification, you risk a fine that starts at €135.

I’ve been outside three times, always for the same reason: the supermarket. Twice I went on foot and was stopped by police both times. On the first occasion, I was told that I was too far from both my flat and my destination — my stubborn two-year-old who is oblivious to the pandemic wanted to take the sea route home. Today, I was told to make my outing sharp; ie no shooting the breeze with Mia, my Slovenian friend who runs the local supermarket. Not that either of us was in the mood to, however.

In Nice, a drone with a loudspeaker took to the skies to reinforce the message to stay at home, just in case it wasn’t loud enough.

I underestimated how intimidating it would be to be stopped by the police along the streets you call home — and these aren’t the friendly local patrol who guard the school gates. As I nervously fumbled for my driver’s license in my purse this morning, I could feel the patience of the policewoman seeping out. "How am I meant to see your name if you have your finger over it," she snapped at me as she snatched my ID from my hands.

But, apart from that, for me, quarantine life hasn’t taken much to adapt to. As a writer, I work from home and with a four-year-old and a two-year-old, the extent of my social life these days is a glass of wine in front of Netflix. My teacher husband has turned our bedroom into his Google classroom and we have a decent-sized terrace for the girls to play on. I know, however, we’re only four days into something that could last weeks, if not months.

Finding silver linings

Some friends have even texted to admit that they’re enjoying it so far — it helps that the sun is shining. I haven’t been surprised to hear people saying that barbecues have been dusted off from their winter slumber. After all, along with the butcher, many bottle shops have decided to remain open — along with croissants and cigarettes, wine (and steak tartare) has clearly been deemed essential to life here in France.

There are other positives, too — like the fact we’ve finally said hi to the neighbours in the building across from us. Like many cities across Europe, the whole of Nice is throwing open their windows at 8pm every evening to applaud the hero health workers at the frontline of the pandemic.

While it’s true that some of our neighbours seemed to have fled, perhaps to stay with relatives who have large homes with gardens, where we live is normally quiet, so on that front, little has changed. On a normal day outside of the summer season, we get little passing traffic. But, when I’m sitting out on my terrace I’ve noticed that the noise of the trains as they pass along the bay of Villefranche sounds more like a roar than a rumble. And that’s made me realise that this is more than quiet. It’s stillness. And that’s eerie.

The whole of Nice is throwing open their windows at 8pm every evening to applaud the hero health workers at the frontline of the pandemic.

Of course, there’s noise from other sources. My daughter’s teacher emailed during the week and casually mentioned that she and her husband were in quarantine as three of his colleagues have been diagnosed with the virus. The deacon who lives across from us tells me his cousin is in ICU in Paris. "I heard three cases were diagnosed today in the village," drops one of the school mums into our WhatsApp group chat. Christian Estrosi, the mayor of Nice reveals he’s tested positive for the virus. Then, yesterday, there’s an announcement that Prince Albert of Monaco has, as well.

We’re healthy — but that’s not something we’re taking for granted. "It feels like it’s getting closer," my husband said to me the other night, putting into words what I had been feeling.

But, despite this — and the stories coming out of Northern Italy and the warnings from local authorities — some people still don’t seem to get it. On the first night of lockdown, someone posted on a local Facebook group that groups of friends were still drinking on the beach in Nice. A similar report from a friend in Juan-les-Pins, along the coast near Cannes, the following day. People were using the exercise clause as a reason to see friends or to spend hours too far from home. A Nice Matin reporter even met a woman sunbaking topless on the beach, incredulous that she had been barred from indulging in her favourite pastime.

Yesterday, beaches around the country were closed. In Nice, a drone with a loudspeaker took to the skies to reinforce the message to stay at home, just in case it wasn’t loud enough.

Postcard from the future

Today, from the confinement of his own home, Estrosi made a double announcement: he’s closing the city’s emblematic Promenade des Anglais and imposing a curfew from 11pm to 5am in the city. Obviously, many people here still haven’t understood the gravity of the situation.

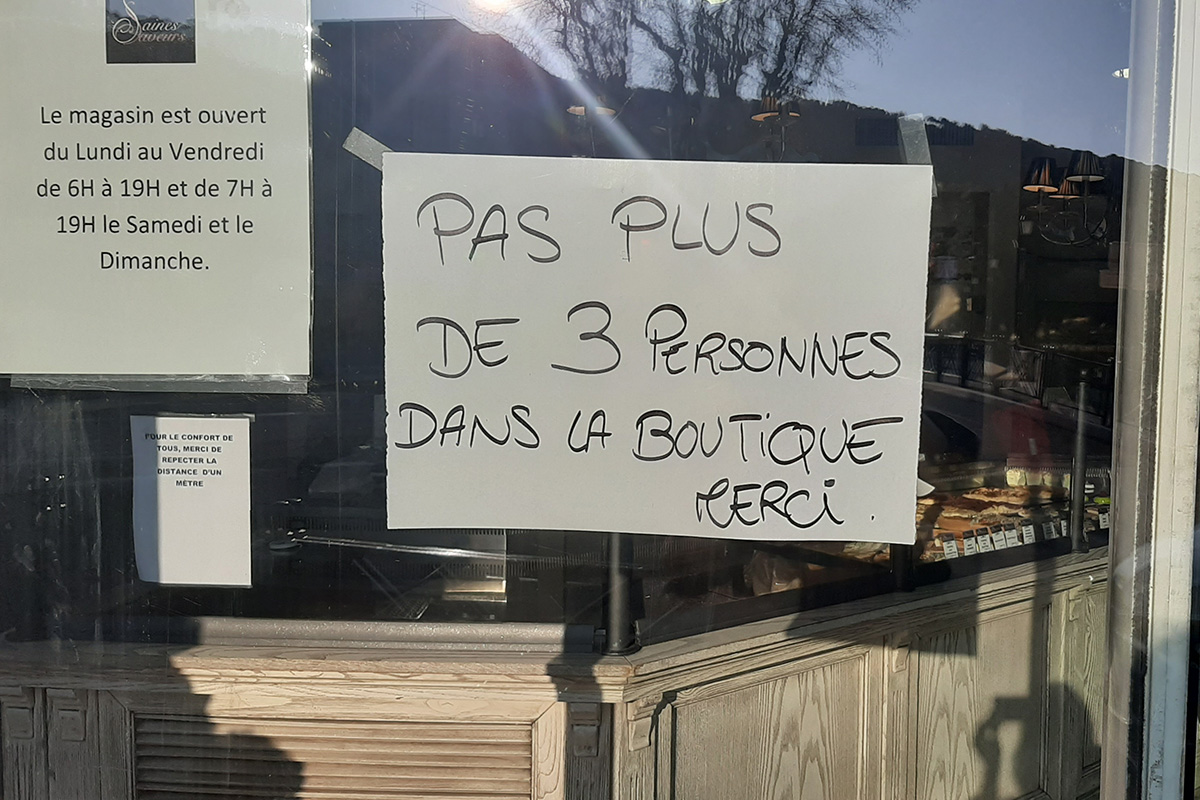

I visited Alessandro again today to restock (not hoard) more salami and he said to me that he still doesn’t think we understand. But what a difference a week has made. This time last week, France had 3,661 official cases. Now, it has close to 11,000. The virus took the lives of 627 people in Italy today alone.

I too feel an increasing sense that others don’t get it, especially back home in Australia. And it’s starting to make me panic. Pictures of bathers shoulder-to-shoulder on Bondi Beach today. Reports of busy Friday evenings around the nation’s capital cities. Perhaps what’s making me most nervous is the family members who are innocently sharing their busy social lives on social media. I want to shout: Stop!! Don’t you realise the scale of this? This is not a drill.

My reality could very easily be yours tomorrow, which is why I’m sending this as a postcard from the future. #flattenthecurve