Billionaires playing games

Billionaires, it turns out, have very similar daydreams to the rest of us – the slight difference being that they tend to make theirs come true.

Ask any serious sports fan and they’ll tell you they’ve toyed with the thought that they’d do a much better job of running their favourite team/franchise/shirt-selling megabusiness than the muppets currently in charge.

If you’re a sports fan and a Russian oligarch valued at US$10.8 billion, you can just snap up a giant Premier League team like Chelsea, partly because the executive seats at its home ground looked sweet, and partly to play fantasy football with real money.

But Roman Abramovich, who paid US$179 million for the club back in 2003, didn’t become the world’s 140th richest man by spending his millions frivolously and was predicting enormous growth in the football industry.

He was right, of course, as soccer has become an evermore profitable game in the 15 years since, capable of raising enormous TV revenues yet also paying out astronomical salaries.

Abramovich’s desire to be the best, and win things, has led him to spend lavishly on the best players and coaches, splashing out a whopping US$2.5 billion during a period in which the club has made losses of more than US$800 million.

Chelsea has, however, won some big trophies to the delight of its fans, including the Premier League in 2005 – something the London-based franchise had not managed for 50 years – and the Champions League in 2012.

And Abramovich must still be enjoying himself, because he turned down a US$2.5 billion offer for Chelsea from the UK’s richest man, Jim Ratcliffe, earlier this year.

Love or money

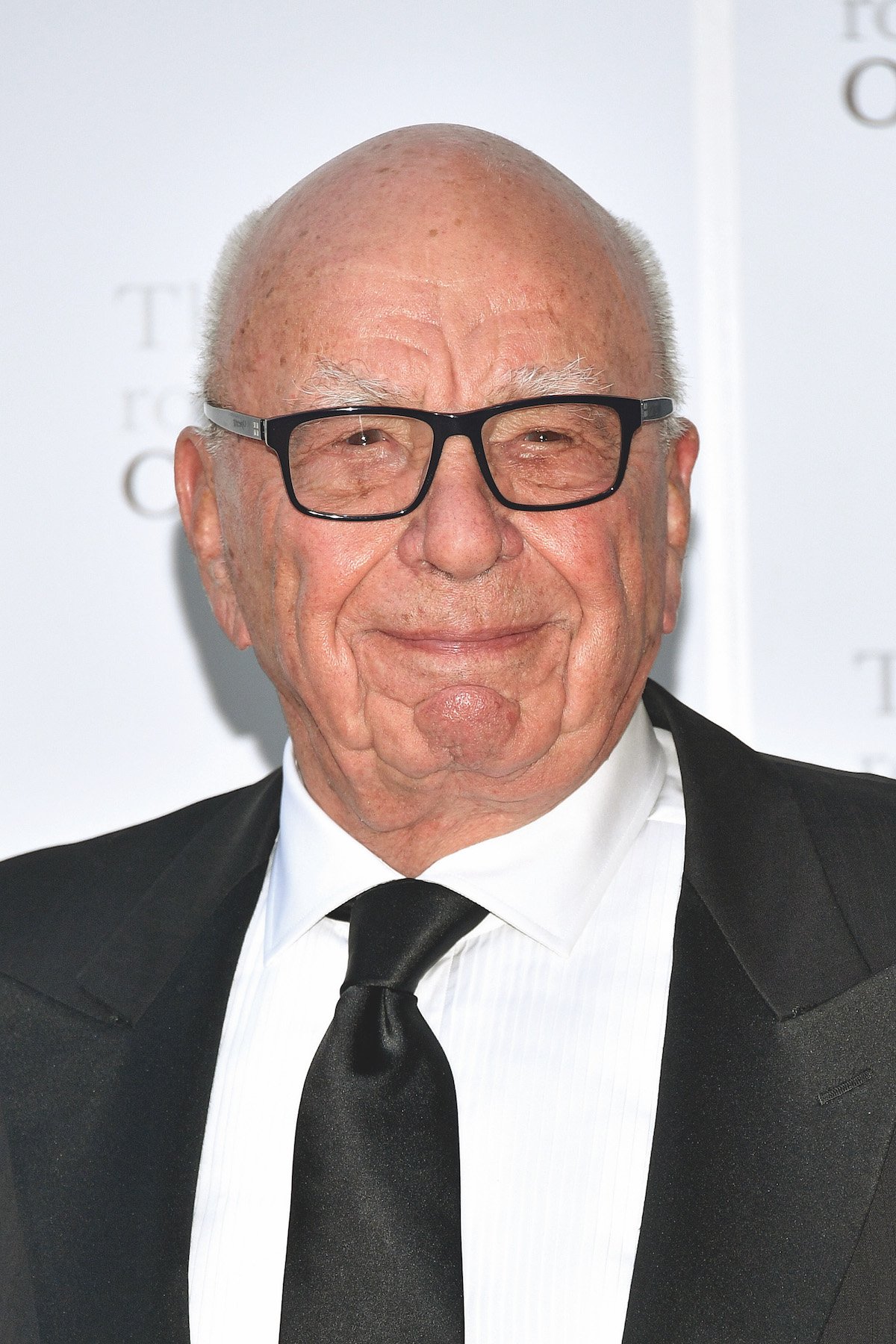

So, is his a cautionary tale? Is buying a sporting team merely a way for the very wealthy to divest themselves of a lot of money, or can it be a good investment? One of the world’s most famously ruthless billionaires, Rupert Murdoch, clearly thought so.

He became one of the forerunners of mighty mogul team owners when he bought the Los Angeles Dodgers for US$320 million in 1997, despite having so little interest in baseball that he’d never even seen a game live.

Murdoch bought the team, and its stadium in LA, as a way of helping his Fox network drum up viewers for a game he figured could make him some ad dollars. Sure enough, the Fox network had seen a big rise in baseball audiences by the time Murdoch sold the Dodgers to Frank McCourt, a Boston-based billionaire, in 2003 for US$450 million.

According to Forbes, McCourt – a property developer – made roughly US$2 billion in pre-tax profit by the time he sold the team, and its now highly valuable real estate, in 2011. Remarkably, he turned all that profit despite being hated by the team’s fans, and going to war with Major League Baseball, which effectively forced him to sell up.

That kind of home-run return, married to a love of a particular team, or sport, has seen a huge rush of billionaires buying up big clubs.

According to a report from UBS and PwC called ‘Billionaires Insights’, more than 140 of the world’s top sporting teams are now owned by a competitive group of just 109 billionaires.

More than 140 of the world’s top sporting teams are now owned by a competitive group of just 109 billionaires.

Acquiring sports teams is a growing trend in Asia, where more than half of the club acquisitions by minted individuals took place in the past two years. At this stage, 60 of the sports-team-owning billionaires in the world are from the US, with 29 from Asia, and that number looks like it will be growing.

Social change

When it comes to high-dollar sports, it’s hard to go past the booming cash cow that is the Indian Premier League (with a brand value of US$6.3 billion). Indian billionaire Mohit Burman is a co-owner of the Kings XI franchise and says rich people flashing their cash on sporting teams reflects a shift in social attitudes in Asia.

"Previously, it wouldn’t have been so acceptable to be seen spending a lot of money on a sports team, but that is changing now," he says. His own decision to buy into the IPL when it kicked off 10 years ago was driven only partly by the fact that he admits to being "a massive cricket fan".

"I definitely saw it as an investment," Burman explains. "At the same time, though, I knew it could be difficult to make money owning a sports team – I was well aware of what I was getting into. You shouldn’t invest money that you can’t afford to lose into sports."

"You shouldn’t invest money into sports that you can’t afford to lose." Mohit Burman

Having money you can afford to lose is, obviously, one of the defining characteristics of billionairism. Burman, who has also owned badminton and hockey franchises in India, has enjoyed the excitement of owning an almost-winning team, though, with his Kings XI reaching the finals of the 2014 competition and narrowly missing out on the big prize.

Sadly, doing well on the field doesn’t always mean the same for the balance sheet, he says. "When you win games, your players want to be paid more, although when they don’t do so well, the opposite certainly doesn’t apply."

Like many hugely rich sports fans, Burman is keen on buying a football team, and he’s been involved in negotiations with several English clubs but says he’s still waiting for the right opportunity.

He could, of course, sell his share of the Kings XI, which has certainly gone up in value since its inception, but he says only, "I’m not a seller." It seems he’d like to win the IPL at least once before cashing out.

Perhaps the most successful – as well as infamous – investor in sporting teams was US real estate mogul Malcolm Glazer, who bought the American National Football League team the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 1995 for US$192 million (current value US$1 billion) and then purchased the slightly more high-profile Manchester United Football Club for US$1.4 billion in 2005.

The deal for United caused an outpouring of outrage from its vast global fan base after it came out that Glazer had leveraged the club’s assets and borrowed against them to complete the deal.

It’s been estimated that, since then, more than US$1 billion has come out of the club’s earnings to service that substantial debt and pay dividends to the owners – who are now Glazer’s widow, Linda, and their six children. (Glazer died in 2014.)

The Glazers have overseen a period of remarkable financial returns from the club, which would net them more than US$4 billion if they were to sell it today. Rumour has it, however, that the family has developed a real sporting passion for the club and refuses to let it go.

It probably helps that United is now a money-making machine, netting profits for the family of US$42 million in 2016–17. In 2017, Forbes rated Manchester United as the most valuable football club in the world.

Grand gestures

Aside from sporting passions or the desire for financial returns, the final factor driving the superwealthy to invest in sports is a certain grandiosity – the same kind that inspires them to buy superyachts or Rolls-Royces.

The UBS and PwC report found that heavy hitters often invested in sport despite advice to the contrary, largely because the price tags for clubs were so large only they could afford them.

One of the co-authors of the report, John Matthews, says he often advised his billionaire clients against investing in the world of sport. "I would tell my clients the fastest way to become a millionaire is to become a billionaire and then buy a sports team."

Buying a globally recognised sporting brand is one way of writing your name in the history books, of course, but it’s also a handy way to make connections. "One billionaire told us that you do not really buy sports clubs for financial returns," the report says. "Instead, it opens the door to amazing people — you sit at the table with ‘stars, sheikhs, famous businessmen, and regular guys from around the world, all in the same room, all talking only about the ball’."

Sport, see? Proving that billionaires and regular guys are just the same.