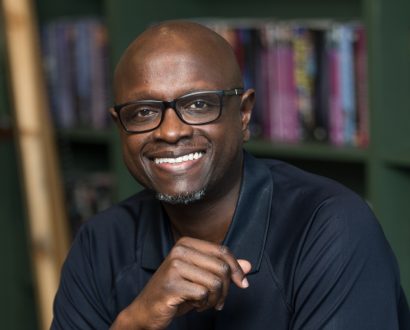

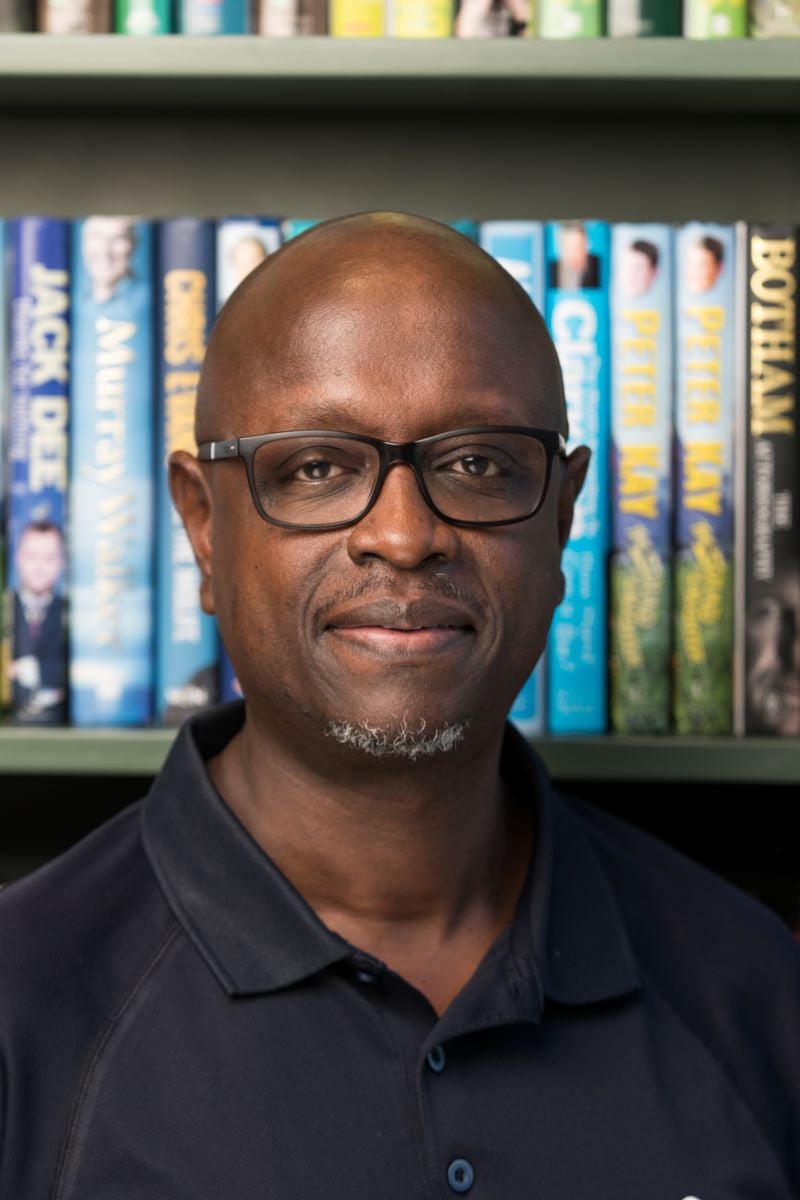

Putting the pieces of a fragmented food market together

Peter Njonjo remembers the moment he realised he could revolutionise the efficiency of Africa’s food industry: he was in the midst of a failure. "My business partner Grant and I had recognised a very interesting opportunity to export bananas, which grow naturally in Kenya, to the Middle East, where there’s a huge need for bananas," he recalls.

After making contact with Middle Eastern companies and taking a very large order of bananas, Peter and Grant set about fulfilling the order through local farmers. "We thought it would be very easy to put everything together," he says. "But, sadly, we couldn’t export a single container."

"We realised how much inefficiency lies in the African food industry, basically due to retail fragmentation."

The pair found the local food industry lacking. The farmers couldn’t offer any traceability, there was no record keeping and agricultural practices were substandard – if they were present at all. "Everything was super informal," Peter says. "People didn’t even know the types of varieties they were growing."

Confronted with this reality and burdened with seemingly worthless stock, a decision was made to pivot: "We decided to sell the bananas locally, but as we did, we realised how much inefficiency lies in the African food industry, basically due to retail fragmentation."

Europe’s food market is controlled by about 10 big retailers, but former Coca-Cola executive Peter says it’s a very different story in Africa. "In a city like Nairobi, there’s around 180,000 retailers through which people can buy food," he says.

"That’s a very, very high level of fragmentation and leads to a lot of inefficiency. We thought if we could find a way to disintermediate the market, there was a significant opportunity there. It was an ‘aha’ moment for us."

Local Insights

Rather than feeling disheartened by the situation, the pair were inspired. Unable to access the wholesale market directly, Peter suggested selling the bananas out of car boots in the informal retail sector. It worked: the entire load of bananas was sold – at a profit.

"I couldn’t believe that the pricing at retail was higher than the wholesale market to the point that by bypassing wholesale, we could sell at a profit," he says. "That’s what led us to understand why Africans in urban cities are spending a fortune on food in this day and age."

"We’re getting into a space without precedent, so we’ve had to base our progress around small experiments that build the execution muscle to do more."

This realisation also led to the formation of Twiga Foods, a business-to-business food distribution platform based in Kenya. Twiga aims to bring Africa’s food industry in line with the rest of the world by sourcing fresh produce – from bananas and potatoes to maize flour and sugar – from the continent’s myriad farmers and manufacturers and keeping prices fair.

As CEO and Co-Founder, Peter believes that greater social and economic change in Africa all begins with food. "Today, consumers in the US spend, on average, 6.2 per cent of their disposable income on food. In Europe, it’s 8–10 per cent. Africans spend about 50–60 per cent because of how inefficiently it’s produced here," he says. "But if you produce food efficiently, you can significantly reduce the amount of money being spent on food – money that’s then able to be spent in other sectors of the economy."

Local connections

It’s core ideas like this that have set Twiga on a path of reinvention. Backers such as Goldman Sachs have signed on to the tune of about US$60 million to be a part of what Peter believes will be revolutionary for Africa.

"Every Tuesday and Thursday I spend time with customers," he says. "I go out to the streets and talk to the little retailers to find out what they think of what we’re doing.

"Every month, we’re serving 50,000 retailers and, for us, that’s a testament that we’ve managed to find a model that works in terms of recruiting and retaining customers. We’ve also attracted amazing talent, which has helped us figure out what we need to do to start lowering the cost of food."

"So far, Twiga has driven the price of bananas down by 15 per cent or more."

From the outset, the platform was imbued with big ideas and what Peter calls an iterative approach to strategy development. "The market doesn’t like change, and it won’t transform or adapt that quickly," he says. "In our case, we’re getting into a space without precedent, so we’ve had to base our progress around small experiments that build the execution muscle to do more."

So far, Twiga has driven down the price of bananas by 15 per cent or more. "For us, that’s been a huge achievement, but when we can get 20–30 per cent below the market price, that’s when we’re achieving what we set out to do."

Twiga’s pioneering ideas have thus far been accepted by the market, which consciously or otherwise recognises the urgent need for change. Peter’s vision is to expand the Twiga model across the African continent over the next five years.

It’s a mammoth task, but one he believes is not only possible – it’s crucial. "If you’re going to pursue something, then assume a big, transformational vision," he says. "That way, the result of that effort will always be satisfying in terms of the legacy you want to build."